Stereotypies are those movements or sounds that may look like tics to someone unfamiliar with autism. Yet they are very different — both in how they appear and in what purpose they serve. They are regular, repetitive, rhythmic, and seemingly without purpose. Seemingly is the key word. In reality, they play a role in sensory and emotional regulation. In short, they are essential to the life of an autistic person. In autistic communities, we often use the term stim. It’s the autistic version of the word stereotypy, which is more clinical and carries a negative connotation.

📋 TL;DR : My stims in a few words

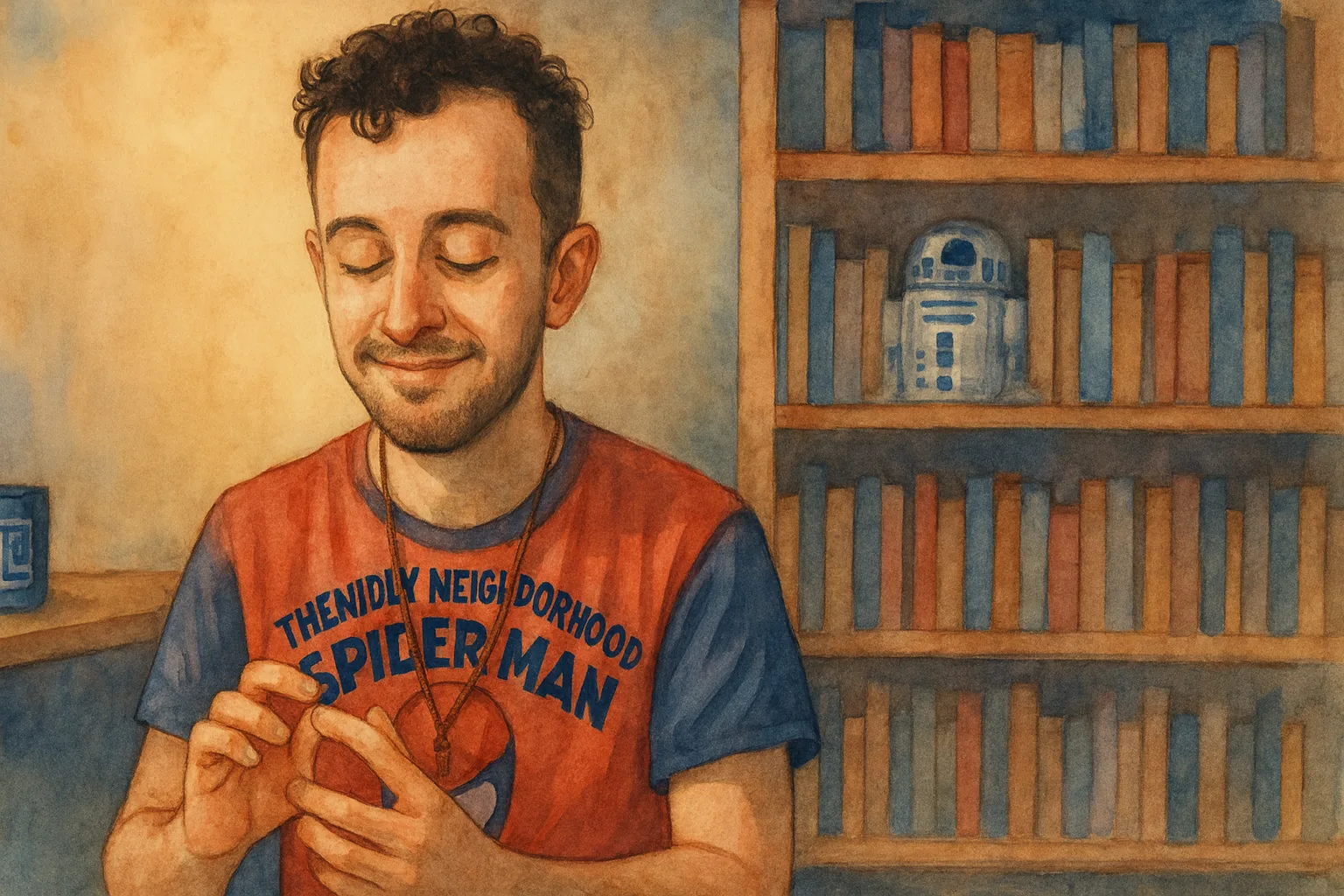

- Tactile: tracing the outline of my nails, playing with my necklace, pressing firmly with my fingers.

- Visual: lining up objects, staring at patterns, watching dust float in a beam of sunlight, mentally simulating scenes.

- Auditory: humming, listening to the same sounds on repeat, tongue-clicking, repeating sentences for their rhythm or musicality.

- Oral/Gustatory: chewing salt, biting objects, putting my necklace in my mouth.

- Olfactory: smelling gasoline at gas stations, seeking certain pleasant natural body scents.

- Proprioceptive: rocking, deep pressure, tight hugs, muscle contractions.

- Vestibular: spinning in circles, walking quickly, bouncing when I’m happy.

- Cognitive: sorting files or photos for hours → mental regulation.

The difference between stimming and tics

Stereotypies often appear very early in childhood—typically within the first 24 months. According to one study (PMC), 80% of cases appear before age 2. Tics, which appear later, are instead sudden, irregular, and non-rhythmic (DSM-5). Tics are commonly found in the allistic population, whereas stimming — performing a stereotypy — is specific to autistic people. Stimming is often experienced as soothing and pleasant.

For example (before I overwhelm you with my long list of stims): I stroke the edge of my thumbnail with my index finger all day long, and the sensation of my finger sliding is absolutely magical. It calms me when I’m overloaded and stimulates me when I’m watching a film or working.

Stims are often partially unconscious (at least until I notice I’m doing them). To finish distinguishing them from tics: tics are usually accompanied by a sudden internal urge or discomfort that is only relieved by performing the tic (I experience some myself and can confirm how overwhelming that urge can be). Suppressing a tic often leads to a buildup of internal pressure that’s difficult to tolerate.

Stimming, on the other hand, can generally be stopped — even if doing so may create discomfort for the autistic person. So what exactly is stimming — and what role does it play?

The role of stimming

The biological role of stimming

Stopping myself from stimming feels like being prevented from expressing a part of who I am — a need just as essential as eating. It’s biological. I remember once telling someone that my father had commented on how “strange” it was that I moved my fingers while listening to music, and I felt the need to hide it. She asked how that felt, and I simply replied: “horrible — but other, more discreet stims took over.”

You can suppress the behavior, but the need always comes back. When I talk about sensory regulation, the role of stimming is twofold: to compensate for sensory understimulation, or to neutralize excess sensory input. This explains why rocking in a noisy environment doesn’t add stimulation — it actually helps reduce it (even if that seems paradoxical). I explore sensory sensitivities in more detail here.

When anxiety rises — much like someone tapping their foot — stereotypies intensify. That’s normal, because research has shown that stimming activates dopaminergic pathways (Frontiers in Neuroscience — Motor Stereotypies). In simple terms: it releases dopamine — the brain’s reward chemical — in significant amounts.

For those who enjoy the neuroscience: recent studies also show involvement of the fronto-striatal circuitry (the network responsible for motor control and emotional regulation). Stimming also affects attention — it’s very common to see autistic people stim while focusing on an activity or working.

A form of communication in its own right

Autism involves differences in nonverbal communication, and paradoxically, stimming can become a form of nonverbal expression. People often think of hand flapping when an autistic person is happy, or bouncing on the spot for the same reason. In those cases, the stim acts both as a way to regulate an emotion that feels too intense, and as a way to expressthat emotion outwardly.

When my mask started to fall apart, I noticed myself stimming whenever I felt strong emotions — stims I had suppressed for most of my adolescence suddenly resurfaced. Reconnecting with them felt like recovering a part of myself I had forgotten.

A few tips for loved ones

If there’s one thing to remember, it’s this: never force an autistic person to stop stimming. If the stim becomes harmful (for example, hitting my head with my hands during a crisis (which I sometimes do)), the best approach is to help the person find safer alternatives, not to suppress the behavior altogether.

It’s important to understand the stim before judging it. In the end, that’s often what we need most: understanding. Creating an environment where stimming is accepted — not merely tolerated (which implies enduring it) — makes a huge difference. Acceptance means recognizing that stimming is part of identity, not a malfunction.

All of this shows that stims are not just a medically described behavior. They are an integral part of who I am. To deny or suppress them is to deny a part of me. That’s why, beyond sensory regulation, there’s also a political dimension: the right to stim.

Rather than explaining this in abstract theory, here are some concrete examples — they speak far better than a long academic paragraph ever could.

My stims

I have many of them — most serve sensory regulation. Some appear when I’m overwhelmed by emotion; in those moments, they act as emotional regulation, yet they’re always intrinsically tied to sensory processing.

My sensory stims

These are the ones that resurfaced first during my initial autistic burnout and later through unmasking. Some have been present since childhood — the ones subtle enough not to “bother” others. They help me regulate the constant flow of sensory input that overwhelms me as soon as I leave my home — or fill the gap when sensory stimulation becomes too low.

TL;DR : My stims categorised

👇🏻 Tactile:

- Tracing the outline of my thumbnail, the most pleasant and satisfying stim

- Holding my necklace and spinning the pendant (helps me focus)

- Pressing my nails into my thumb

- Finger flicking (like tapping a marble with one finger at a time)

- …and its alternative: tapping each finger one by one with my thumb, in rhythm with the music (also a game to follow the tempo perfectly)

- Pressing my hands together and pulling them apart repeatedly

👁️ Visual:

- Aligning objects (tables, counters, shelves)

- Staring at repetitive patterns (tiles, my cinema poster cards on the wall)

- Watching dust particles floating in a beam of sunlight

- Mentally simulating scenes (internal visual simulation)

👂🏻 Verbal/Auditory :

- Clicking my tongue in rhythm with music

- Humming — with or without background music

- Listening to the same tracks on repeat

- Rewatching trailers repeatedly because of the music

- Repeating a line from a movie if I like its rhythm or musicality (a form of echolalia)

👄 Oral/Gustatory :

- Eating coarse salt

- When I was a child, after coming back from the beach, I would chew on my seatbelt in the car because it tasted like salty seawater.

- Putting my necklace in my mouth and spinning the pendant (also visual and proprioceptive) to taste the metallic flavor.

👃🏻 Olfactory:

- Taking deep breaths at gas stations

- Smelling pleasant natural body scents

- Smelling leather (some of my collector Blu-rays are bound with it)

- Smelling old books

- The scent of glue or solvents

- Burning incense from time to time

🚶 Proprioceptif :

- Swaying side to side

- Sitting in a tightly curled posture

- Tight hugs

- Stretching or tensing muscles

- Fidgeting with my fingers when I’m very uncomfortable (also visual)

- Rocking back and forth intensely when anxious

- Leg bouncing (when I’m happy or emotional) + clapping my hands (when I’m very happy), often with a wide smile and teary eyes

- Bouncing on the spot (when happy but standing)

- Hitting my head with both hands during a meltdown (autistic crisis) — a way to release overwhelming emotion.

🎢 Vestibulaire :

- Pacing in circles during phone calls or while brushing my teeth

- Walking quickly in the street

- Tilting back and forth on a chair (seeking a slight loss of balance)

In a context where I’m alexithymic (meaning I struggle to identify and understand my emotions), I now rely on my stims to help me recognize what I’m feeling.

And what about cognitive stimming?

It’s one of the hardest ones for me to identify — even though in hindsight it was suspiciously obvious. I sometimes spend a lot of time sorting through my files or photos. I once renamed and reorganized every file stored in my cloud with a precise naming structure. It took about seven hours of work in a single afternoon — and I was genuinely delighted doing it.

Similarly, earlier this year, over the course of two days, I decided to sort all my photos stored in the cloud (to relax — and to “reduce my carbon footprint” (even though the impact was negligible)). I deleted roughly 1,500 out of 3,000 photos. And beyond sorting them, I went through them one by one to identify missing faces and add missing locations.

After that, I decided to download literally every administrative, medical, billing, or prescription document into my cloud. I wanted to be prepared for any situation in which a document might unexpectedly become useful. (A mobile phone bill from February 2016 probably isn’t, I’ll admit — but it didn’t escape the purge.)

I then found myself mildly distressed when I discovered that while I had downloaded all my phone bills up to April 2020, I had stopped afterward — and it’s no longer possible to retrieve anything prior to May 2023 from the provider. So 36 invoices are gone forever — deeply frustrating — and with them, a piece of my inner peace. My need for completeness felt directly attacked.

It added up to a total of 45 hours of work — and once again, it did me a lot of good. I was deeply focused on the task, and afterward, I felt relieved. Reducing the number of photos meant reducing a mental weight tied to everything I considered unnecessary. What I felt afterward was a kind of mental silence, as if I had just completed a puzzle. In the end, this form of cognitive stimming is closely connected to sensory stimming: organizing files relies on visual processing, and naming them engages the verbal part of the brain.

🧠 TL;DR : Keep in mind

- Sorting my files, photos, and documents for hours to clear my mind.

- Renaming, organizing, and categorizing with extreme precision (e.g., cloud storage, invoices, faces).

- Deleting what’s unnecessary → a feeling of relief and inner order.

- Reviewing my collections (films, music, writing) to revisit familiar patterns.

- Mentally repeating or restructuring ideas — like rearranging pieces of a puzzle.

Originally published in French on: 11 Sep 2025 — translated to English on: 18 Nov 2025.