Autistic burnout, in a few words, feels like a long-term complete shutdown. It often follows sensory, emotional, or cognitive overload and usually results from extreme compensation (social masking) that has pushed the autistic person beyond their tolerance threshold. Masking is a constant daily effort, activated the moment the person is interacting or exposed in public.

The few existing studies on autistic burnout estimate its average duration at around 3 months (National Autistic Society). However, every autistic person is different, and every burnout experience is unique. It can therefore be shorter, or last several years, especially if the triggering factors remain present. It’s important to understand that autistic burnout is a massive crisis caused by the accumulation of many heavy and overwhelming demands placed on the autistic individual.

📋 TL;DR : Autistic burnout in short

- Collapse after overload + prolonged masking.

- More “I want to but I can’t” than “I don’t want to anymore.”

- What collapses: energy, executive functioning, sensory tolerance.

- It is neither laziness nor a lack of motivation.

- Solution: deep rest, reduced stimuli, adjusted expectations.

My first autistic burnout

I experienced my first autistic burnout at age 25, just a few months before receiving my autism diagnosis. In fact, it contributed to that conclusion after depression was ruled out (I know the symptoms well, and they are different). After a long period of intense socializing to expand my social circle (because I believed it was necessary if I ever wanted to have a relationship (when I thought I wanted one, while in reality it was only social expectation)), I suddenly crashed. I went from needing at least 10 hours of sleep to recover from going outside, to sleeping 16 hours a day — despite staying locked indoors with the blinds closed to block out all light disturbances.

At that point, I was completely confused, and that’s when I eventually came across what was then described as Asperger’s Syndrome, and shortly after, Autism Spectrum Disorder as a whole. As I continued researching, I stumbled upon the concept of autistic burnout and began wondering if that was what I was experiencing. I was extremely cautious: I spoke about it to people around me, but I always added a layer of doubt (and years after the diagnosis, I still maintain some of that doubt — for reasons I’ll explain in a future article).

Since I wasn’t diagnosed yet, I didn’t feel legitimate claiming the condition. Even with my autistic friend, whom I met in a discussion group for autistic people, I sometimes felt the need to clarify that my possible autism wasn’t officially confirmed.

However, evidence kept piling up. The sudden, brutal collapse fit perfectly with every description of autistic burnout I was reading.

The symptoms of autistic burnout

The first sign that struck me was the extreme intensification of my sensory hypersensitivities — unlike anything I’d experienced before. All my compensatory strategies had to be reworked. A friend even reminded me recently that, during that intense period, I once met him in a bar while wearing my noise-cancelling headphones the entire time. It made conversation difficult, but it was necessary if I wanted to avoid staying home completely. It was already a huge effort just to meet him in a bar, so I had to protect myself from the sensory chaos.

Light

Chaos is the right word. During this burnout, even the slightest ray of sunlight or the glow of a neon sign felt blinding — to the point where going grocery shopping, even with sunglasses, would push me straight into a shutdown. I had to find strategies such as having groceries delivered or even ordering food, because my wrecked executive functioning made cooking overwhelmingly exhausting. The only moments I felt at peace were when I was at home, or walking through the city at night — where I switched into an extreme sensory-seeking mode.

Sound

Same pattern with noise. Everything became too much. I could no longer tolerate Parisian city sounds or traffic, and I couldn’t handle social gatherings with more than one or two people. I still occasionally forced myself to go out, mostly for logistical reasons, and every single time it ended in a meltdown. A bit masochistic of me, but I genuinely wanted to function. I simply couldn’t anymore.

Touch

The third sense most affected was touch. The only physical contact I could tolerate was the ritual hug with my best friend, it calmed me. Any other form of touch felt unbearable, to the point where unexpected contact (two knees brushing, a fabric touching my skin) triggered intense reactions. This is where it clearly differed from depression for me — depression had never caused that level of heightened sensory sensitivity.

A real-life moment of sensory chaos

I remember standing in a crowded street. I briefly removed my headphones while looking for someone — and felt instantly attacked. I could hear a stroller rolling 20 meters away, clothes rubbing, footsteps, cars, fragments of conversations in every direction, honks — everything layered over everything else. I couldn’t distinguish sounds anymore. Nothing filtered. I often say that, in those moments, my senses erupt. This is when I’m at the highest risk if I don’t protect myself quickly.

So during that burnout, I had autistic crises one after another. And the magic — or rather the curse — of autistic burnout is that some consequences remain. My sensory sensitivity never fully returned to baseline — everything stayed much more intense.

In short, the burnout sharpened senses that were already razor-sharp.

Reduced executive functioning

Executive functions include all the cognitive processes used for planning, inhibition (resisting impulses), task-switching (cognitive flexibility), and working memory. In autistic people (and in ADHD), these functions are often impaired (Autism Awareness). During a burnout, they are commonly drastically reduced — especially because they are overused in constant social adaptation.

Planning

Planning becomes affected, making every task feel either urgent or impossible to complete. This is what I explained earlier with the example of cooking: it requires several consecutive steps, and when planning breaks down, the task turns into a cognitive challenge and the autistic person may begin avoiding it.

Reduced inhibition

Reduced inhibition results in the sensory hypersensitivities I mentioned earlier, but also in a collapse of social masking: the autistic person no longer seems able to compensate. Doing so would be too exhausting, and the brain forces this loss of capacity as a form of protection. Remember: hiding a stim or a ritual requires energy for an autistic person. By allowing these traits to resurface, the brain is conserving energy.

Increased rigidity

Flexibility may decrease, resulting in stronger rigidity in the autistic person. This may manifest as (intense) autistic crises (shutdowns or meltdowns) triggered by the slightest change in plans or unexpected event. This is not a tantrum — it is a neurological protection response.

Working memory

Finally, working memory. When affected, the autistic person may experience memory gaps, difficulty working, or difficulty understanding verbal instructions. They may need written support to function at their best. While many autistic people already process written instructions better than spoken ones, this becomes especially pronounced during autistic burnout.

I completed an IQ assessment during my diagnosis process, and my working memory score was noticeably lower than the score I had received four years earlier, when I was first identified as highly gifted.

Extreme fatigue and highly specific interests

During my first burnout, I essentially did three major things: sleep 16 hours a day to recover from constant cognitive overload, lie on my couch watching all ten seasons of Smallville—a former special interest I immersed myself in—and read dozens of articles and studies about autism.

I immediately warned the medical team assessing me that I already knew a lot about autism, out of fear it might bias the tests (spoiler: you can’t cheat all the tests). And honestly, I approached the tests like a challenge, wanting to “succeed” (spoiler #2: some results proved I was far worse than I thought at nonverbal reasoning and social conventions).

My special interests were the only thing capable of giving me even a small amount of energy amid the sensory and emotional chaos. Burnout drained me completely. I felt exhausted:

- Sensory-wise: as already mentioned, the slightest ray of sunlight could trigger a crisis, so I avoided going out during the day.

- Socially: talking for more than 20 minutes could lead me to shutdown.

- Emotionally: I was hypersensitive 24/7.

- Physically: getting up from the couch required enormous effort.

This is also where it differs from depression, and why comparing symptoms matters.

A possible confusion

With depression

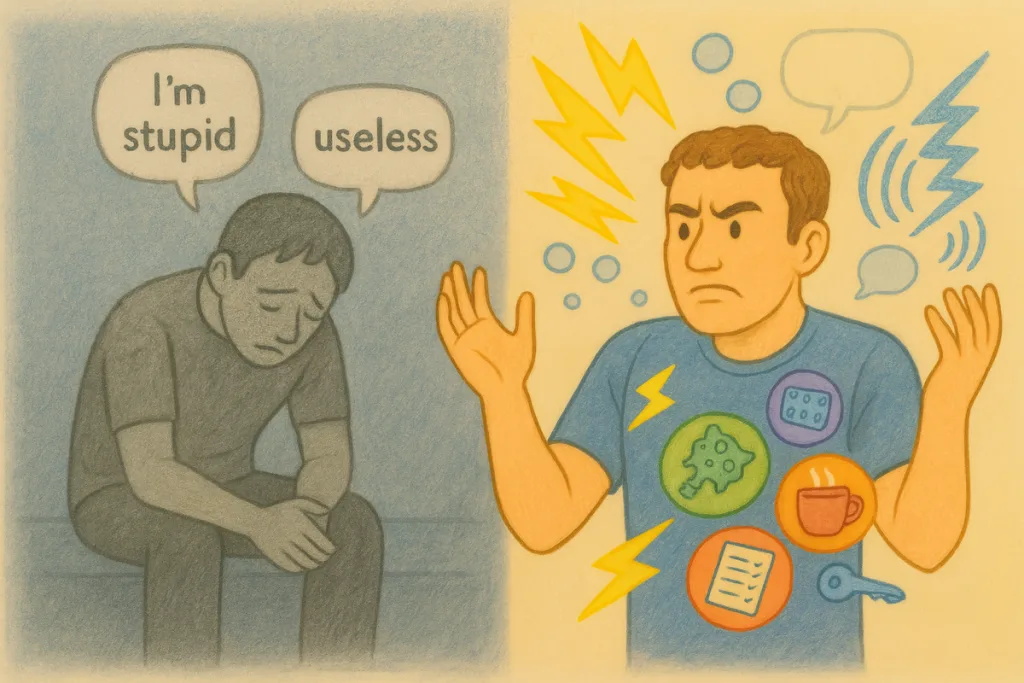

In a depressive episode, the person is not just exhausted. They also experience anhedonia, meaning a loss of pleasure in activities they normally enjoy, or no desire to engage in them at all. In autistic burnout, there is typically no loss of pleasure: there is a loss of capacity. It’s not that the autistic person doesn’t want to do things, but they cannot do them. Autism Speaks describes the difference between depression and autistic burnout in more detail.

Depression is a neurochemical imbalance, whereas autistic burnout is neurological in origin. One is a dysfunction; the other is a protective shutdown. Burnout is also typically not accompanied by the sadness or guilt listed among diagnostic criteria for depression. Instead, autistic burnout often includes anxiety — sometimes intense frustration — linked to this drained battery preventing functioning.

Depression = I’m worthless, I’m useless.

Autistic burnout = I’m overloaded, I can’t function anymore.

Depression is treated through therapy and sometimes medication, whereas autistic burnout requires environmental adjustments to remove stressors, withdrawal and sensory rest, and a reduction in masking. It is not an illness. It is a neurological response that requires modifying one’s environment in order to gradually recover.

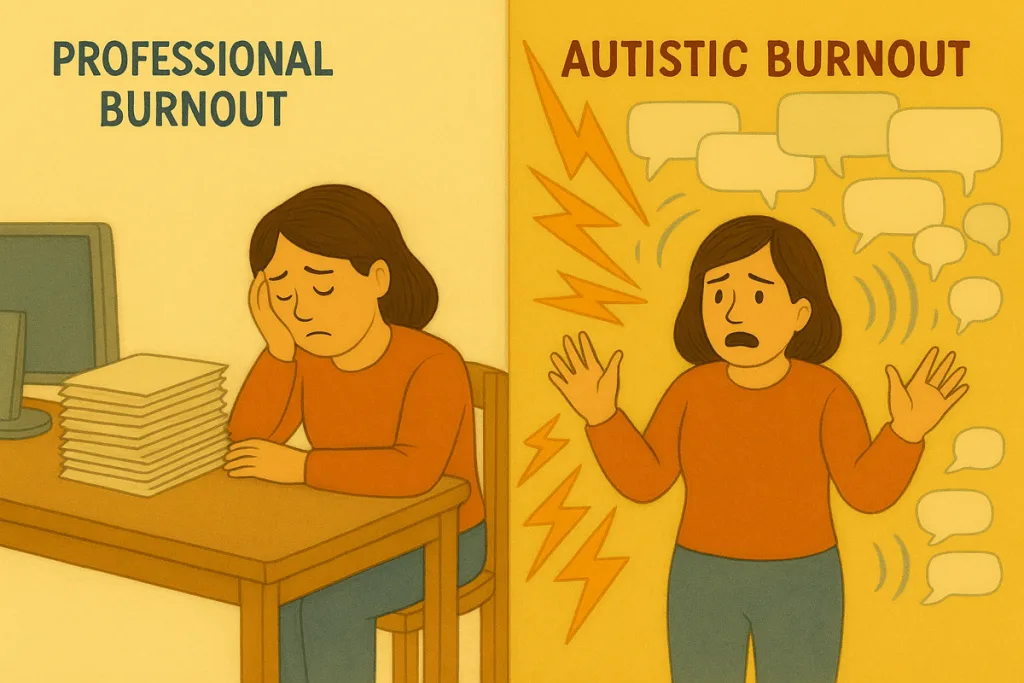

And with professional burnout

It should also not be confused with classic professional burnout, which stems from work overload, lack of recognition, chronic stress, or hierarchical pressure. While autistic burnout affects sensory, emotional, social, cognitive, and physical aspects — and does so suddenly — classic burnout tends to appear gradually and shows mainly emotional and physical exhaustion.

Rest and addressing the source of professional burnout usually allow recovery, whereas autistic burnout can last for weeks or months even after removing the stressors. The latter requires rethinking one’s entire lifestyle and often breaking compensation strategies that were developed over years or even decades. Executive functioning is also less affected in typical professional burnout.

To go further, AdvancedAutism offers a list comparing classic burnout and autistic burnout — for those who aren’t afraid of English.

Strategies

During autistic burnout, the main priority is to get away from situations perceived as dangerous or overwhelming, likely the very triggers of the burnout. Stimming, isolation, and listening to one’s body become essential.

It’s also important to step away from both external and internal expectations (including perfectionism, which is common among autistic people). The priority is rest, even if that means sleeping most of the day. It’s also crucial to allow yourself to do nothing, without guilt: burnout is a neurological need, resulting in an inability to function at full capacity.

After burnout

Although I’ll explore this more deeply in a dedicated article, a few words are necessary about recovery, which usually happens gradually (unlike the sudden onset). Burnout often leads to redefining personal boundaries, understanding them better, and expressing them — something that should be done without hesitation.

Autistic burnout often appears alongside the collapse of social masking, and sometimes masking returns once the crisis has passed, which can lead to additional burnouts. It’s important to remember that burnout is the brain’s way of signaling that the autistic person has reached the limits of masking, and that it may be time to prioritize personal needs rather than functioning at full capacity for the sake of appearing “normal.”

For some, burnout also triggers an autistic coming-out. That was my case: gradually informing people around me about my autism, always with the fear of being judged. It was a necessary step toward understanding myself better, and toward greater acceptance.

In a few words, autistic burnout is a warning signal telling the person experiencing it to stop worrying about the image they project, turn inward toward their primary needs, and allow themselves to exist authentically. The crisis can create intense emotional and sensory distress, and that reality must be acknowledged when supporting an autistic person.

📋 TL;DR : Keep in mind

- Trigger: prolonged overload + masking → brain at its limit.

- Nature: neurological collapse — not a lack of willpower or laziness.

- Symptoms: extreme fatigue, heightened sensitivities, impaired executive functioning, difficulty performing even simple tasks.

- Internal experience: “I want to, but I can’t anymore.”

- Management: reduce expectations, limit stimuli, allow deep rest and time alone.

- Recovery: slow, gradual, non-linear — requires adjustments and new boundaries.

📚 To dig deeper

Explore Autism hub, which brings together all my resources on autistic crises, sensory overload, routines, and autistic functioning.

Originally published in French on: 16 Nov 2025 — translated to English on: 22 Nov 2025.