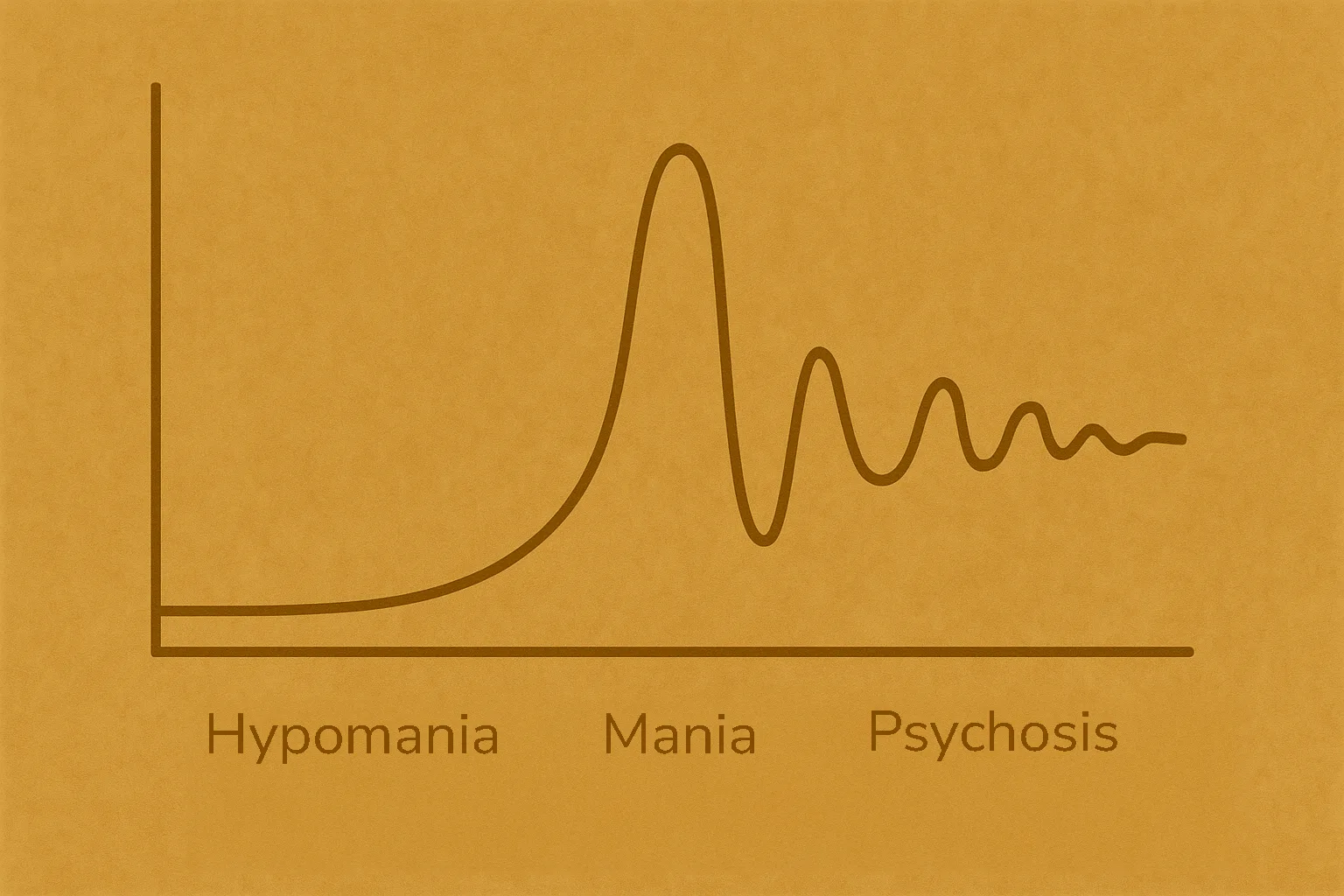

The manic episode, for all people with bipolar type I, is the logical continuation of the hypomanic episode. Sleep is drastically reduced and energy multiplies. The person seems to behave more and more abnormally. While hypomania can go more unnoticed, the manic episode completely alters the functioning of the bipolar person. The individual appears extremely euphoric, laughs very easily, makes puns, jumps from one idea to another, multiplies projects, has grandiose ideas, and in the most severe cases, may decompensate (psychosis).

📋 TL;DR : Mania in short

- 🌪️ Mania = the continuation of hypomania, but in an extreme version.

- 😴 Almost no sleep, unlimited energy.

- ⚡ Euphoria, grandiose ideas, risky behaviors.

- 🌀 Possible delusions and hallucinations (psychosis).

- 🏥 Often requires hospitalization.

The specific DSM-5 criteria

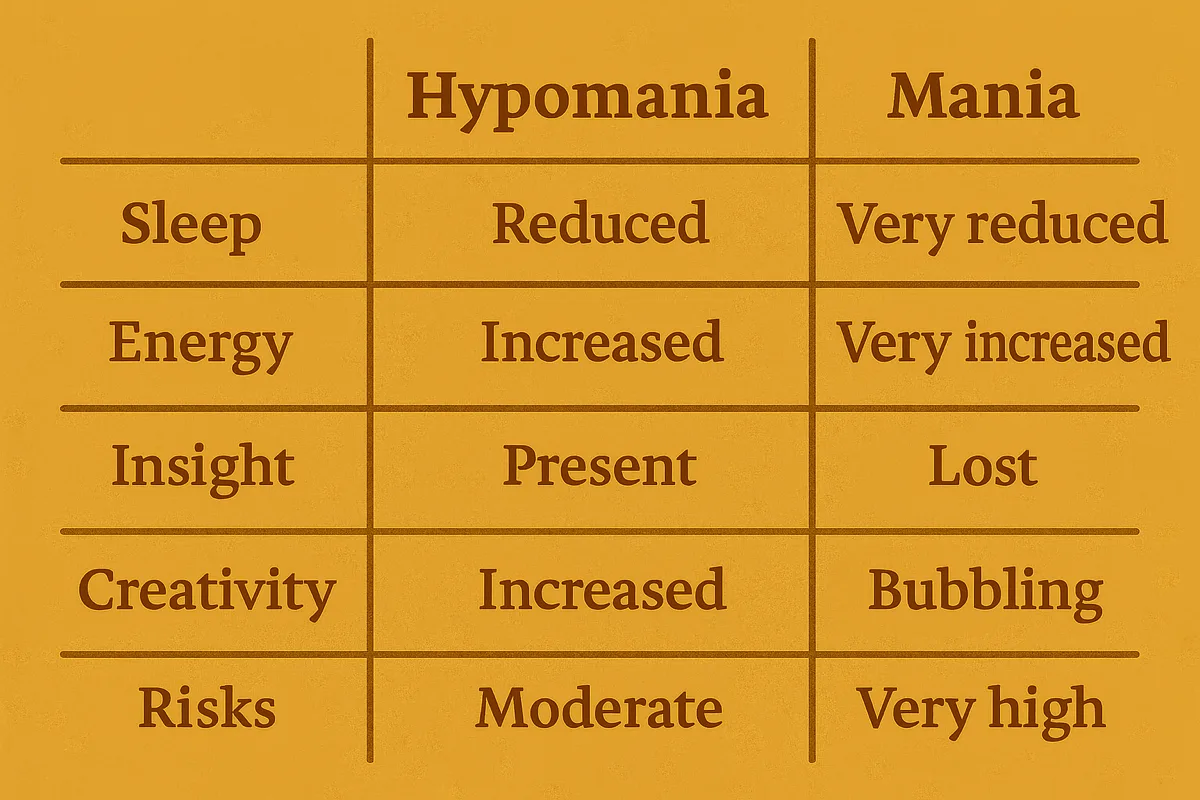

The manic episode is characterized by the same symptoms as the hypomanic episode. What distinguishes it is its intensity and its disabling nature. When all the symptoms escalate to the point that they make the patient completely dysfunctional, require hospitalization, or present psychotic features, the episode is automatically classified as manic. Psychosis occurs when the manic episode involves a complete break from reality: delusions and hallucinations. These are the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-5 (the diagnostic manual for mental disorders) used to distinguish hypomania from mania. If the diagnosis was type II, it is rediagnosed as type I. This is why some patients are mistakenly diagnosed as type II before receiving a corrected diagnosis.

How the episode is treated

Unfortunately, the nature of the disorder influences how it is treated. Particularly with antipsychotics in type I, which also act as mood stabilizers. Traditional mood stabilizers are often not enough to stabilize a person with bipolar type I. So IF antipsychotic is absent → manic episode at risk → psychosis. A study reports that 50 to 75% of people with bipolar disorder will experience a psychotic episode in their lifetime. Another study published in 2022 mentions a rate of 57% psychotic features in mania and 13% in depression. This highlights the importance of making the correct diagnosis.

Transition from hypomania to mania

The transition to a manic episode is often not sudden. Warning signs appear, particularly the total loss of insight (the loss of awareness of one’s mental state, explained in my article on hypomania). It is not systematic (I am often able to identify that I am in an episode when my symptoms become too intense) but it is common. And even when insight is present, the episode often manifests through a total refusal of outside help. The person simply believes they are doing very well. This can stem from stopping treatment, which can amplify the nature of the episode.

In a manic episode, behavioral disorganization is also common. The person becomes scattered, constantly jumps from one activity to another, engages in extreme compulsive purchases, inappropriate social behaviors (talking too loudly, hypersexuality, aggression), and a chaotic lifestyle (loss of temporal cues for sleeping, eating, and neglected hygiene). They become completely dysfunctional.

My account of a manic turn

Sometimes I go through hypomania before entering mania, and sometimes the shift is abrupt. I can flip in less than 48 hours, even though some signs are often present for weeks beforehand. And the more episodes I have, the faster the turn. It’s a total short-circuit. I go from needing a good ten hours of sleep (12 if I had intense social interactions the day before) to less than 3 or 4. Euphoria takes over quickly and intensifies within a few hours. Ultra productive. Then scattered. Then counterproductive. I can spend hours drinking coffee continuously and staring at a pattern while letting myself be flooded by electric waves of energy running through my entire body. Continuing my medication? Ancient history. Doing everything to keep my instability stable? A goal.

We are therefore far from the hypomanic episode. It’s an entirely different dimension that strips the patient of the freedom to control their own body. They often let themselves be guided by a completely altered state of consciousness.

Major differences with hypomania

The manic episode is distinguished by the intensity of the symptoms. A patient who overspends during a hypomanic episode generally remains under control. In a manic episode, spending often becomes massive, sometimes reaching several (tens of) thousands of euros in just a few weeks or even days.

The manic person is also prone to extremely risky behaviors, whether multiplying unprotected sexual partners or driving dangerously. As an example, I gave up the idea of driving out of fear of the manic turn. Driving while manic resulted in an accident that could have had devastating consequences. When I drove in that state, I saw traffic lights as an obstacle, and I didn’t hesitate to run them or break every speed limit trying to beat my own records. The manic episode provokes constant seeking of stimulation and adrenaline.

The manic episode has sent me to the hospital several times, whereas I usually remain functional when I’m hypomanic. When a patient is diagnosed and the environment informed, a hypomanic episode can often be identified, but it is the manic episode that leaves the biggest mark. When I wasn’t taken to the hospital, it was because I narrowly escaped the police and my loved ones weren’t there to witness the phenomenon. A phenomenon worth detailing.

The manic episode in detail

The manic episode is distinguished by various observable symptoms from an outside perspective.

Its key symptoms

Loss of insight

I mentioned this earlier in the article and explained it in detail in my piece on hypomania: loss of insight is one of the most common symptoms in a manic episode. It refers to the loss of the ability to judge one’s own mental state — in this case, the abnormal way the affected person acts and thinks. The patient is no longer aware that they are ill and often rejects any confrontation on the subject. In their mind, they are fine and haven’t changed.

Acceleration of thought

This is known as tachypsychia, often accompanied by a flight of ideas. Thoughts seem to burst forth like an endless stream of overlapping ideas that prevent the person from focusing on a single thought. This flow is very overwhelming and can be perceived as either euphoric or distressing, especially as the episode intensifies. This also leads to extreme talkativeness: the person doesn’t stop speaking and can chain conversations together without ever tiring.

They often monopolize discussions around themselves. While autistic people are self-centered in a structural sense, bipolar people in mania may appear egocentric. From personal experience, I can describe tachypsychia as an endless and extremely fast stream of thoughts fighting with a melody playing nonstop in the background. The ideas compete for first place, but my brain no longer knows how to sort them properly.

Grandiose ideas

The line is thin between simple grandiose ideas — a fundamental diagnostic criterion of mania — and grandiose delusions, which mania can lead to. The person experiencing them has big projects and often feels invincible, sometimes like a god. When they lose complete contact with reality and only these ideas remain, this is considered psychosis.

Psychosis

This is the extreme consequence of the most severe manic episodes. It is estimated that between 40 and 60% of manic patients decompensate. Psychosis, in bipolar disorder, is a symptom of mania. It includes hallucinations and delusions. The most common delusions are grandiose delusions, mission delusions, delusions of reference, and erotomania (the false belief that someone is in love with you).

I almost always decompensate when I am manic, particularly into grandiose delusions (my first episode included the idea that I was one of the most intelligent people on the planet and destined to solve world hunger) and erotomania, which convinced me that a woman was madly in love with me (accompanied by false beliefs that I had feelings for her). The feeling of being “crazy” has been traumatic for me on multiple occasions.

Stopping treatment

The manic episode also often includes stopping medication. Irregular medication adherence is already high (between 30 and 50% of patients) and increases further during manic episodes. The process generally unfolds like this:

Hypomanic episode triggered → undetected → gradual intensification → borderline manic turn → stopping treatment → explosion of symptoms.

This is something I have experienced many times, as I almost always stop all my medication at the beginning of a manic episode, often to boost the episode. It is one of my first signs that something is wrong (or that things are going a little too well), because usually, I avoid bipolar episodes like the plague. The logic is that the patient often believes they no longer need help, sometimes that they are simply doing well, and therefore no longer need medication.

They may also stop them simply to amplify the euphoric state (which is often my case) because mania is deceptive: it makes the bipolar person believe they will remain in this state forever. Trying to bring them back to reason by mentioning depression is therefore often futile.

Its consequences

Depression

Like hypomania, the manic phase often inevitably leads to depression. The crash is even more brutal. This is normal: the brain has exhausted all its neurotransmitters and has gone beyond the threshold normally tolerable for a neurotypical person. It’s important to understand that a bipolar person can go for entire weeks or months with radically reduced sleep. When all energy is depleted, the brain crashes into depression.

Therefore, it’s not only the manic episode that must be treated but also the depressive episode that commonly follows. Having lived through extremely brutal crashes, and having come to despise mania, I strongly encourage people with type I to find strategies and not lose hope. With experience and proper treatment, manic episodes can be avoided or contained to prevent depressive episodes.

Hospitalization

Already mentioned above, hospitalization is often necessary during a manic episode in order to treat the patient as quickly and effectively as possible. Hospitalization can be a traumatic experience for many, in addition to the shame patients may feel afterward. In the most severe cases, it can also result in mechanical restraint — that is, physically tying the patient to the bed. This occurs when the patient is too agitated to be safely contained or must be prevented from harming themselves. It is (normally) a last resort and has a limited duration.

From testimonies found in books, online, and from a friend of mine, the experience is sometimes so traumatic that mentioning it can be disturbing for them.

My autism is strongly influenced by my manic episodes.

Autism and mania

Unlike hypomania, which manifests as an intensification of my autistic traits, the manic episode destroys almost all of them, except for stimming. I lose my routines (showering becomes optional), I have no more rituals, and my sensory hypersensitivities disappear. I can go out in bright sunlight without glasses and navigate a loud social environment without feeling assaulted in my ears. This is also one of my main symptoms that sometimes alerts me to my state.

Stimming is the only thing that remains. That makes sense because its purpose is sensory regulation but also emotional regulation. In a context where all emotions are amplified, stimming becomes a strategy my autistic brain maintains while my bipolar brain accelerates.

According to a Spectrum News article, up to 30% of children diagnosed with bipolar disorder are also autistic.

Compensation strategies

I have already detailed my monitoring strategies in my article on hypomania (mood-tracking apps, sleep tracking, etc.). In mania, these tools often become ineffective because I lose all ability to self-assess.

In hypomania, they can still help me stay oriented. In mania, I no longer manage — the data I record is false or missing.

📋 TL;DR : Keep in mind

- Mania is the extreme form of hypomania, specific to Bipolar Disorder Type I.

- Sleep collapses, energy skyrockets, and daily life becomes completely disorganized.

- Euphoria, racing thoughts, grandiosity, and risky behaviours take over.

- A major risk emerges: loss of insight, delusions, and hallucinations — full psychosis.

- It is often triggered by stopping medication and usually requires hospitalization.

- After the manic phase comes a brutal crash into severe depression.

- The impact on social, financial, professional and personal safety is enormous.

- In my case, almost all my autistic traits disappear during mania — except for stimming.

Mania is nothing but an euphoric illusion. It is devastating. This is why learning to recognize the warning signs and having proper follow-up usually make it possible to regain a stable life. It is the daily struggle of every bipolar person.

Originally published in French on: 7th Dec 2025 — translated to English on: 8th Dec 2025.