After having explored autism in detail in my previous articles, it is now time to talk about my bipolar episodes, following the chronological order in which my cycles evolve. When people think of bipolar disorder, they often imagine someone who is sometimes sad, sometimes happy — someone who simply has mood swings (the definition of a “moody” person, essentially). The reality is far more complex. With bipolar disorder, a person oscillates between euphoric episodes and depressive ones. It is a very serious disorder that requires regular medical care to allow the affected person to function.

📋 TL;DR : In short

- 🌗 Chronic psychiatric illness, not just a simple shift in moods.

- 🔄 Two types: Type I (mania) and Type II (hypomania + depressions).

- ⏳ Diagnosis is often delayed (around 10 years on average).

- ⚠️ High risk: 1 in 5 people with bipolar disorder dies by suicide.

- 💊 Treatment is possible but takes time to stabilize.

This article will be less ironic than the one about autism. Bipolar disorder has never held the same place in my life: it broke me before it taught me anything. So here, I’m taking a slightly more serious tone.

Unlike autism, which is a condition (more precisely a neurodevelopmental disorder), bipolar disorder is a mental illness, a psychiatric one, and it cannot be cured. It can be treated with medication, and treatment can help the person remain stable most of the time once proper care is in place. The earlier the treatment begins, the higher the chances of reaching stability more quickly. Bipolar disorder stems from a chemical imbalance in the brain.

Diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5

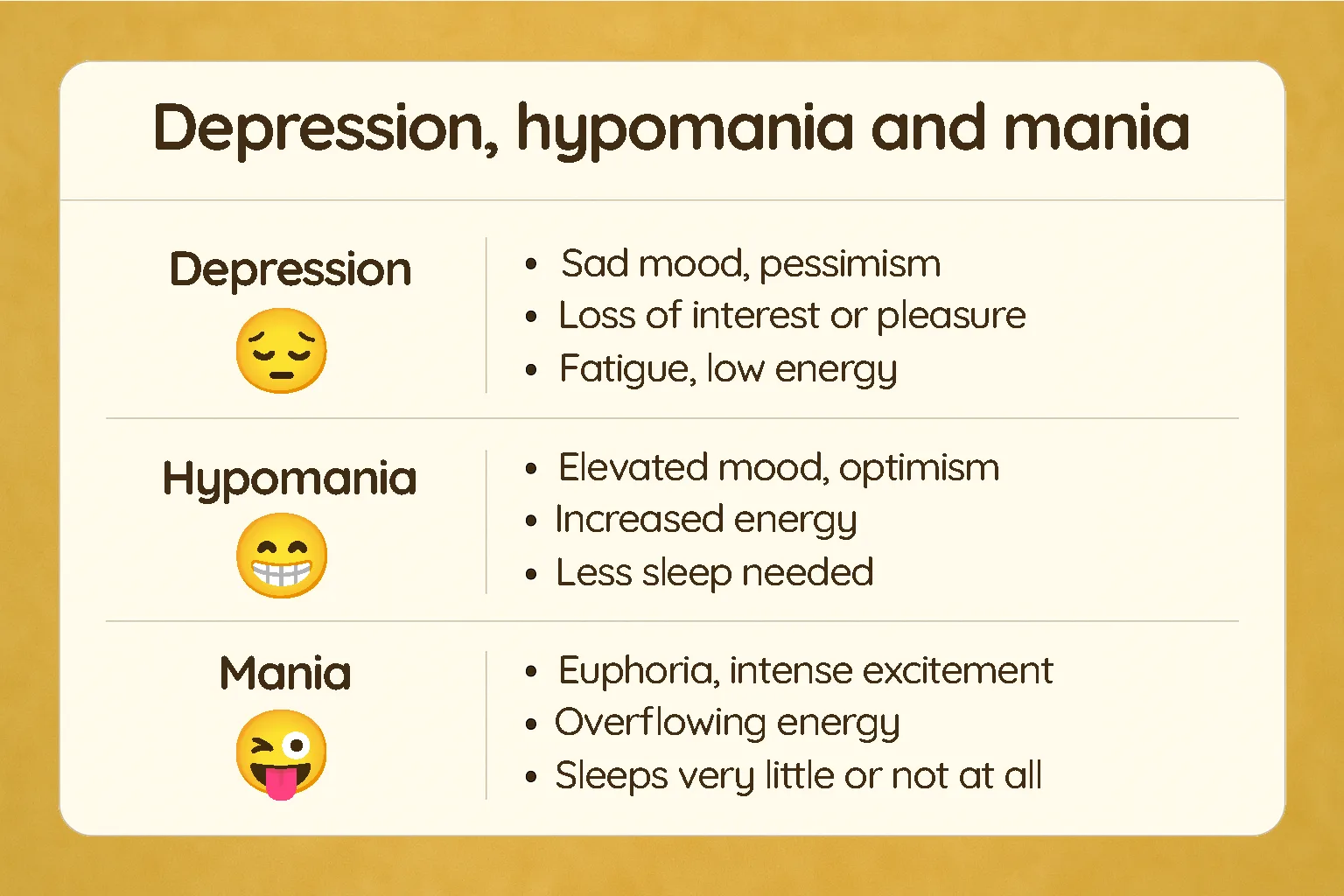

It is therefore a chronic psychiatric disorder that can fluctuate regularly and sometimes very rapidly (what is referred to as rapid cycling when a person experiences at least four episodes within a single year). The intensity, frequency, and duration vary from person to person. The DSM-5 (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) outlines the criteria for diagnosing these episodes, including minimum durations.

There are two types of bipolar disorders, three if cyclothymia is included. Bipolar II disorder requires at least two hypomanic episodes and one depressive episode. Bipolar I disorder may also include these episodes but only requires having experienced at least one manic episode for diagnosis. Cyclothymia is a milder form, alternating between elevated and depressive states that are not intense enough to qualify as hypomania or severe depression. On this blog, I’ll mainly refer to Bipolar I and II (especially I, which is the one I’m affected by).

What’s also important to understand is that Bipolar I disorder, despite having much more severe euphoric episodes, is not considered more serious than Bipolar II. In fact, Bipolar II often comes with much longer and more recurrent depressive episodes, and is therefore often at higher risk for intrusive dark thoughts and suicidal ideation. Where the disability in Bipolar I mainly comes from the severity of manic episodes (the dramatic ones you hear about in the news), Bipolar II shows its severity primarily through depression.

Types of bipolar disorder

Bipolar I disorder

Bipolar I disorder may involve only manic episodes, but they are most of the time followed by a major depressive episode, often extremely intense when it comes after a very high euphoric phase. I call it a crash — as if I had been flying higher and higher until a sudden failure caused an emotional crash. A manic episode is a euphoric or irritable state so severe that it often requires emergency hospitalization.

While it may seem tempting, even addictive, it is in reality deeply destructive for the person experiencing it. It impacts every area of life: social, interpersonal, and professional. It leaves the person completely dysfunctional. In its most severe form, the person may decompensate: this is psychosis, accompanied by delusions and hallucinations, requiring immediate intervention to prevent harm.

After a manic episode, the person is often extremely exhausted (depleted of neurotransmitters and physiological resources). The system collapses and shifts into depression. Based on my experience, the longer the manic phase lasts, the longer and harder the depression tends to be.

Bipolar II disorder

Bipolar II disorder is characterized by hypomanic and depressive episodes. It never reaches full mania. If it does, if hospitalization becomes necessary or if psychotic features appear, the diagnosis is reevaluated as Bipolar type I. Hypomania is the episode many people fantasize about. The person appears happy (more precisely euphoric), more impulsive, takes more risks, and is very often extremely productive and/or creative. Like mania, the episode may feel addictive, especially when the person experiences frequent and sometimes very long depressive episodes. Who wouldn’t dream of a brief escape from a life that feels dull or overwhelmingly sad most of the time?

After a hypomanic episode, a depressive episode almost always follows. Many people with Bipolar type II experience this cycle daily when untreated or when treatment isn’t yet effective. Depression means being constantly sad, losing interest in activities, losing the strength to get out of bed even for the smallest effort, seeing life in black and white. It isn’t about “not trying hard enough,” it’s about no longer being able to. It’s psychological.

Science corner

To make the science a bit more accessible: it’s psychological because — as mentioned earlier — it’s linked to a neurochemical imbalance involving several neurotransmitters: dopamine (the reward hormone), serotonin (the “happiness” hormone), norepinephrine, and glutamate. During (hypo)mania, dopaminergic and noradrenergic activity is abnormally high, which leads to hyperactivity, impulsivity, and exhilaration (The Role of Neurotransmitters in Bipolar Disorder, 2025). In contrast, during a depressive phase, these systems function at a much lower level, contributing to slowing down, sadness, and loss of motivation.

This imbalance doesn’t act alone. Recent research shows differences in brain structure in certain regions (the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, limbic network…), which may contribute to emotional dysregulation (Wikipedia).

During diagnosis, patients are often asked about family history. That’s because there are genetic predispositions involved. A person does not become bipolar. They are born with a genetic vulnerability, with a risk estimated between 50% and 85% (Barnett et al., 2009). Media often bring up drug use (cannabis especially) as something that can cause the disorder. Toxic substance use cannot create the condition in someone without predisposition, but it can trigger the illness in someone already vulnerable.

Two types, equally serious

Bipolar disorder (both types) is often considered the second most severe and disabling psychiatric disorder — or tied for first place alongside schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (Burden of Mental Disorders, PMC). This is why comparing the severity of the two types makes little sense: both make daily life extremely difficult for those affected.

Equally serious for different reasons

Because every person is different, and since Bipolar type II is more likely to involve long depressive phases while Bipolar type I may include only mania, the experience varies. For many years, I faced extremely intense and long-lasting depressive episodes (far more frequent than my manic ones — which were usually yearly — and also far longer). They wrecked my ability to function and pursue my studies the way I would have wanted. And yet, I was diagnosed relatively early — five years after my first manic episode and multiple depressions — compared to the average diagnostic delay of… ten years. That delay is colossal, and there are many reasons for it:

- The stigma: mental illness is scary, so many avoid seeking help.

- Minimization by peers and family: “It’s just a phase,” “It’ll pass.”

- Illusion of rarity: we believe disorders like this are too uncommon to apply to us.

- Fear of diagnosis: being labeled “crazy” holds people back.

- Misleading media: sensationalized portrayals distort reality.

- False assumptions: seen as a “personality flaw” → “get it together,” “your fault.”

- Confusion with depression: especially in Type II, where hypomania goes unnoticed.

- The deceptive high: during elevated phases, you don’t feel sick, so you don’t seek help.

And yet, the diagnosis is not nearly as rare as people assume, and its prevalence is consistent worldwide. Someone once told me that people in poorer countries “don’t have time to be depressed.” Yet they are affected at the same rate as everyone else.

Bipolar disorder also differs from major depression in intensity. The depressive drop is often much steeper and far more intense than in a standard major depressive episode. This is one of the main reasons the risk of suicide is significantly higher, making bipolar disorder the leading psychiatric condition associated with suicide.

📊 Key figures

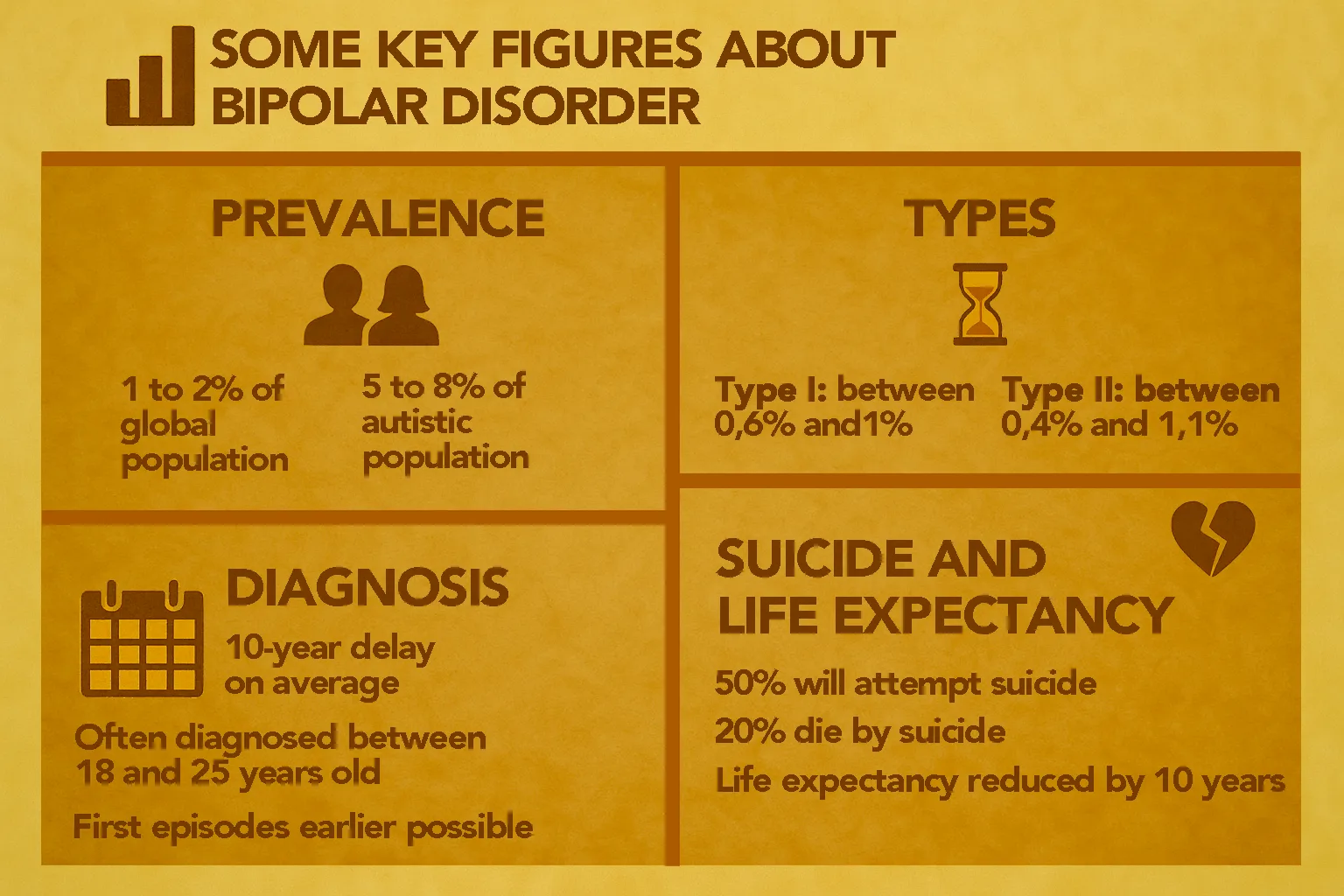

- Bipolar disorder affects 2.4% of the global population, according to a 2023 study.

- Including cyclothymia, prevalence rises to 4%.

- Type II: 0.4% of the population.

- Type I: 0.6%.

- Autistic people are affected at a rate of 5–8% depending on the study.

- Diagnosis typically happens 10 years after the first episode.

- The average age of diagnosis is between 18 and 25, but first episodes can appear as early as 14 years old (and sometimes much later).

- Suicide attempts: about 1 in 2 people with bipolar disorder will attempt suicide at some point in their life.

- Mortality: 40–50% of these attempts are fatal

→ around 4–19% of people with bipolar disorder die by suicide, according to a 2024 study.

→ approximately 15–20% according to another study in The Lancet. - Life expectancy is, on average, reduced by about between 8 and 12 years (PubMed).

- Mortality: 40–50% of these attempts are fatal

The concrete impact

In everyday life, managing bipolar disorder can be complicated. Many people are unemployed because their episodes severely impair their ability to function professionally. Social relationships can become tense due to (hypo)manic episodes and the irritability that may come with them. Adjusting treatment can take a long time and often requires regular changes in dosage or medication. Some people experience very heavy side effects, such as weight gain (sometimes extreme), and some medications even require additional treatments to counter their own side effects (notably tardive dyskinesia).

If hypomanic episodes can turn someone into an extremely productive person, the same cannot be said for depression — which is the cause of many medical leaves from work. A manic episode, on the other hand, seems to exist solely to destroy the person’s ability to function. Euphoric, yes. Productive, yes — but often toward unrealistic projects. All that energy is frequently channeled into what becomes, paradoxically, a perfectly executed form of counterproductivity.

Bipolar disorder has also been responsible for phases of extreme productivity and unprecedented academic success in certain parts of my studies. When I was hypomanic, I didn’t feel tired, so I could produce an enormous amount of work at a pace no one else could match. That’s exactly what happened during the episode that led to my diagnosis.

My personal experience with bipolar disorder

I experienced my first episode at 16. It was a manic episode. Somehow it went unnoticed — or almost — because my mother had actually considered taking me to see a psychiatrist at the time (something I only learned much later). But those around me mostly saw someone who was highly productive, with grand ideas that seemed only slightly excessive.

I entered my first psychotic state shortly after the episode began, with full-blown delusions of grandeur and complete loss of grounding. What followed was an intense and very heavy depression from which I had to drag myself out just to attempt finishing my final year of high school. I was forced out of bed, cried in the shower, and had no understanding of what was happening to me.

The diagnosis — a relief

The episodes continued, without anyone knowing about my depressive phases, until a severe depression during my studies became impossible to hide and raised concern among everyone around me. A few months later, after developing an intense specific interest in psychiatry, I stumbled upon bipolar disorder — and suddenly everything clicked. Everything made sense. I wasn’t alone and I wasn’t to blame.

Another hypomanic episode (bordering on mania) began shortly after, and when the crash eventually hit, I went to a psychiatrist and walked out with a diagnosis of Bipolar type II. Less than a year later, after a hospitalization, it was updated to type I. But that first diagnosis was enough to bring relief. I didn’t care what the label would mean socially — I just needed answers. And after that appointment, I finally began treatment.

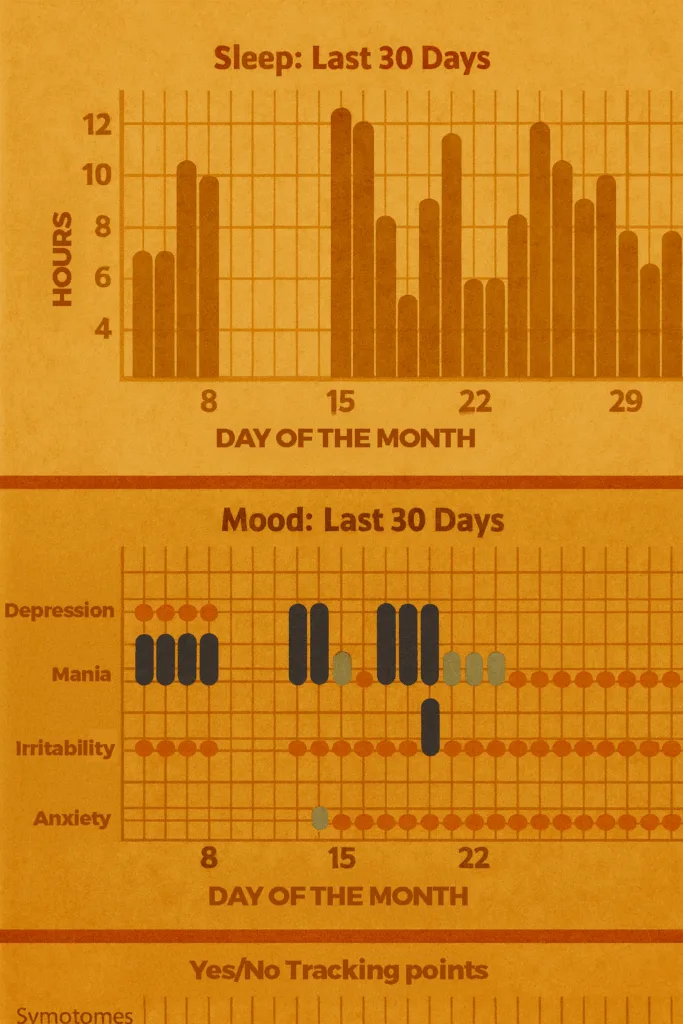

Reorganizing my routines

Fairly quickly, I put different strategies in place to help me navigate the world with bipolar disorder. I had a medication-tracking app and a mood-tracking app where I logged how manic, depressed, irritable, and anxious I felt, along with the number of hours I had slept each morning. The goal was to detect an episode as early as possible. Experience eventually showed me that I stop filling in this app (simply because I forget) during a manic episode — which has become one of the first warning signs, since tracking is normally part of my routine.

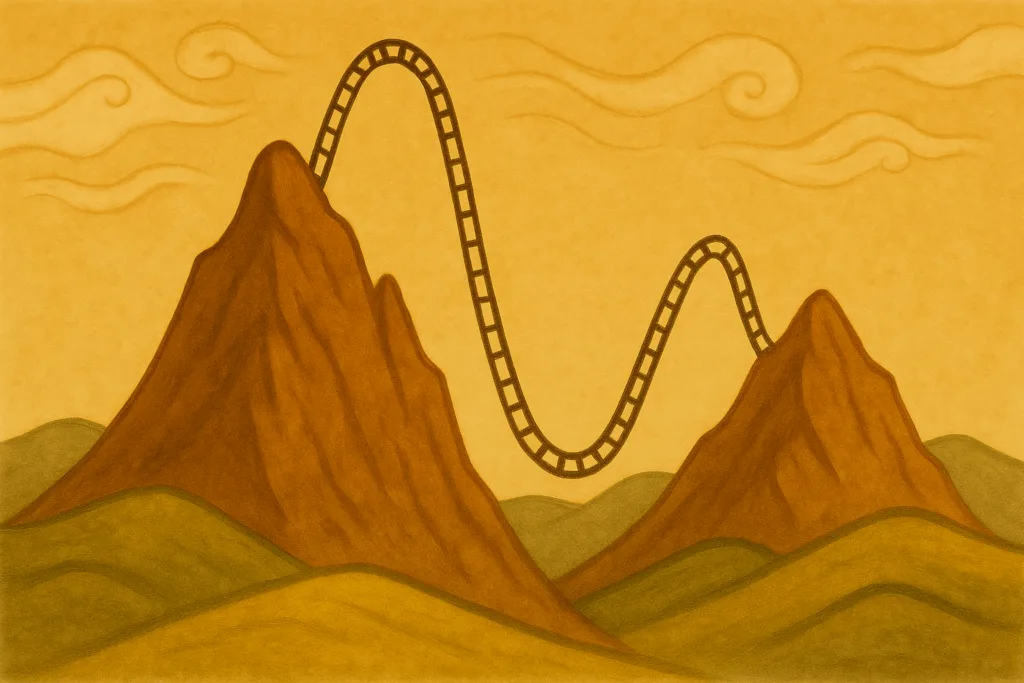

A life-saving diagnosis

Before my diagnosis, I felt like I was constantly on a roller coaster. I was speeding, then slowing down. And the disorder had a huge impact on my substance use and the addictions I eventually had to fight as well. It became two battles: one against bipolar disorder itself, and one against the addictions that grew alongside it. The diagnosis was life-saving. Adjusting treatments took years (and I recently started a new one because my antipsychotic wasn’t working as well anymore).

Reception from others

My social circle was very understanding. Having a name for it explained a lot and made it clear that I wasn’t just being “lazy” when I was depressed. My friends, who had helped me finish my studies, were finally able to understand just how intense the challenges were toward the end. Within my family, it was more complicated: understanding a disorder that felt abstract and distant wasn’t easy at first. But today, I can see that everyone makes an effort — just like I do — to prevent episodes and limit the damage as much as possible.

📋 TL;DR : Keep in mind

- Not a weakness but a severe illness: alternating mania/hypomania and depression.

- Two main types, both serious for different reasons.

- Diagnosis is often delayed → around 10 years after the first episode.

- Prevalence:

- 2.4% (up to 4% including cyclothymia)

- 5–8% among autistic people.

- Life-threatening risk: 50% attempt suicide, 15–20% die from it.

- Treatment can stabilize symptoms, but requires continuous medical follow-up, with sometimes heavy side effects.

- Real-life impact: education, employment, relationships.

- My experience: roller coasters, crashes, but also the relief of a diagnosis and tools to move forward.

What matters most is understanding that bipolar disorder is not a character flaw but a severe illness. Talking about it is already a way of fighting against the years lost before diagnosis.